Showing posts with label Thomas More. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Thomas More. Show all posts

Thursday, February 7, 2019

The Utopian Warfare Mindset and Today

I think that today we share some aspects with the Utopians in our own modern interpretation of war, military structure (not typically drafts), and escalation of conflict (war as a last resort). I'm not a warfare expert nor a history expert, but I feel as though war today benefits more from the Utopian mindset of war than it would benefit the societies of the 16th century. By that, I mean that war is a much bigger risk today with the likes of nuclear weapons and has the potential to affect the entire world. We exist in a globalized society. That's not to say that we are as benevolent as the Utopians and their ideas of an unbreakable truce are; the US specifically has stacked up plenty of war crimes. However, I can see a connection in the notion that the Utopians would regard war with "utter loathing" (98). It speaks to their wisdom and experiences when dealing with war, if not aided by their inherently peaceful nature. With supranational organizations like the United Nations watching over potential warmongering, we have now established Utopian-like preventative measures against war. We have policies in place like sanctions in attempt to keep peace. An all-out war today could result in the complete obliteration of all human life, and it's sad it's taken us until that point to be so hesitant to engage in war. Also, ahead of their time in regards to human rights, "If victory rests with the Utopians, they do not revenge themselves with blood" (103). I'd like to believe that we have become less brutal of a society; we no longer behead people over ideological differences like Henry VIII did to Thomas More. The Utopians were recognize the value of humanity. With the recent suspension of the INF (nuclear) Treaty between the US and Russia and the beginning a new arms race, the world's leaders could look to the Utopians as a reminder of the physical and emotional costs of war.

Wednesday, February 6, 2019

Es muy complicado mi amigo.

Hola mis amigos. Aquí hay una lista de cosas que me resultan complicadas.

1. Spanish. I just dropped Spanish 202. That shits hard, and i'm gonna have to give it another run next semester.

2. Fishing scams at Hood College. How are there so many? And are we just gonna ignore the fact that the man trying to defend us from these scams is named Bing Crosby?! A true unsung hero.

3.The System of Local Government in today's portion of More's "Utopia".

I'm not saying I find chapter 3 good or bad... just that I thought it was a little confusing. It might have just been all the Greek names?

I liked parts. The whole postponement of senate debates thing was funny. More saying he doesn't appreciate when people blurt of the first thing on their mind and then try to defend it. (pg. 64). Kinda sounds like a lot of modern politicians today. I lol'd a little.

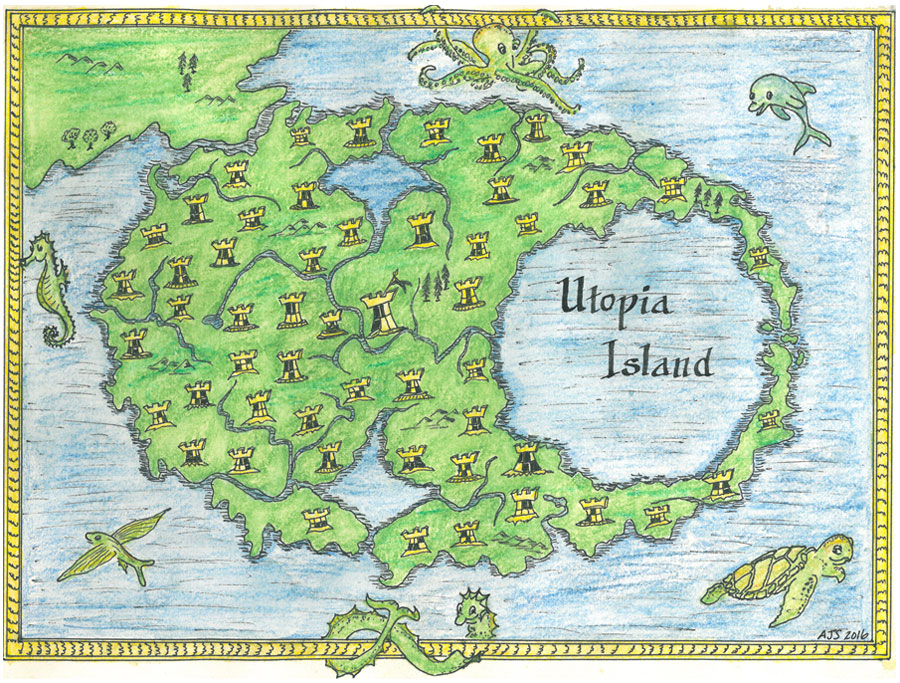

404 Island Not Found

Since Book 2 opens with an explanation of the geography of Utopia, I thought it would be interesting to find an artist's interpretation of what the island might look like. There have been a handful of designs over the years, but I think this one by Andrew Simoson, who applied calculus to the descriptions, might be a more accurate interpretation.

Inside Science article here. Simoson's explanation here.

Inside Science article here. Simoson's explanation here.

Monday, February 4, 2019

Designs of Truth and Nonsense in More's Utopia

As soon as I began reading More's Utopia, I found myself tracking the structure of the text. By establishing a familiar scene (a meeting/feast), readers are encouraged to relax into the dialogue between More and Raphael. The influence of Plato's Republic is apparent, and as such, the discussion of Utopia is broached in contrast to a problem that needs to be solved: England and its noble court. I enjoyed keeping track of the many false or imagined places or terms that appear throughout book one, such as: Polylerites, oligopoly, utopia, Achorians, and ultraequinoctials. The Polylerites are "people of much nonsense," and are used in juxtaposition to the stubborn nobles (More, 41). Their society mirrors that of Socrates' gold, silver, copper, and iron run society. Because of this, I wonder how much of the described England and the briefly mentioned Utopias are meant to seduce the reader with Raphael's arguments - to make us believe that whatever he believes is sensible and correct, as he has 'seen' the impossible world of a utopia. Yet, the dialogue does not serve to bulldoze objections, as More's amused curiosity and warnings highlight the fact that this text is working to encourage questioning of what is right, proper, and desirable in a society. Raphael expressly states that the Utopia's superiority lies within the fact that "their commonwealth is more wisely governed and more prosperous than ours" (More 57). All of this reminds me of our class's circular discussions on what a utopia is and how it can truly be one in the face of human diversity.

In short, I feel that, despite the places and people in book one existing in reality, the constant references to utopia and its laws reveal that this scenario is still imbued with a message and commentary that uses traces of truth to incite conversation and inquiry about peoples' subjectivity concerning 'utopias' and 'Englands' alike.

In short, I feel that, despite the places and people in book one existing in reality, the constant references to utopia and its laws reveal that this scenario is still imbued with a message and commentary that uses traces of truth to incite conversation and inquiry about peoples' subjectivity concerning 'utopias' and 'Englands' alike.

|

| https://i1.wp.com/teacherdavidoh.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/subjectivity.gif |

Skepticism and Utopia

In approaching the reading, I found myself siding more and more with the lawyer rather than Raphael and I truly couldn’t help it. While reading through Raphael’s thoughts on theft, punishment, and government I too was mimicking the lawyer, “He shook his head, screwed up his face, and held his peace” (More; 43).

I found myself questioning every solution that Raphael came up with only to have it later answered in the next sentence (this can be noticed in any of Raphael’s approaches to the discussions, specifically “-not should we accept Stoical rulings that count all offences equal” (More; 40). This was one of the moments where I felt perplexed, but Raphael picked up all of the pieces and presented an answer that would suffice (I think) on the broad spectrum of government and dealing with crime & punishment.

Shockingly, I found Raphael’s expectation of the lawyer’s reply, “-more careful in repeating what has been said than in answering it, so highly do they regard memory,” shaping up to be very similar to my own (More; 39). I was waiting for Raphael to slip up while reading but I couldn’t put together a solid argument besides one major detail I thought important. While a criminal could have his liberty (eventually) and his punishment would be ‘just’ Raphael says that if a convict tried to run away, “-even then his ear would betray him” (More; 42). How do Utopians adjust to their lives post sentencing if half of their ear is missing and how do Utopians treat ex-convicts? If all are equal in Utopia why would they punish someone permanently and mark them in a way that is recognizable to all other people underneath the founding government.

Though this is an analysis of the reading I am wondering why I approached it with so much skepticism. Did anyone else feel like it was such a departure of our own everyday life that they got a little flustered while reading? It seems impossible that a character from 1516 had all of the answers and solutions that would make the world run a little more… smoothly.

(https://giphy.com/explore/white-guy-blinking)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)