Thursday, February 7, 2019

Hippity Hoppity

I certainly like the idea of a society without poverty. The fact that More is discussing a way to bring this about in a period where his ideas did not match up with the current societal values is admirable. Yet while his ideas were ahead of his time, I feel as though one of the biggest issues with them is that they do not hold up in a time like ours where crafts and careers have become increasingly complex. Bear in mind, that is not to say that his ideas are invalidated because of this; as we have touched on in the past, any utopic vision is going to be inexorably linked to the societal context in which it was created. That being said, I would argue that our society has advanced to the point where it would be infeasible to create a market where everything is shared, including jobs. The things we have created - from personal art styles to the iPad I am writing this on - are a product of multiple generations of workers devoting the majority of their lives to developing a single craft to the point where they can be considered an expert in their field. On top of that, these same people often develop their crafts so well because they have a passion for that specific type of work. I feel as though interfering with their pursuits would lead to a decline in the quality of their work. Again, I’m certainly not against social structures designed to eliminate poverty; one of my main career goals is to help the development of such structures. Yet I still feel as though, in our current context, More’s utopic vision falls short of being feasible.

The Utopian Warfare Mindset and Today

I think that today we share some aspects with the Utopians in our own modern interpretation of war, military structure (not typically drafts), and escalation of conflict (war as a last resort). I'm not a warfare expert nor a history expert, but I feel as though war today benefits more from the Utopian mindset of war than it would benefit the societies of the 16th century. By that, I mean that war is a much bigger risk today with the likes of nuclear weapons and has the potential to affect the entire world. We exist in a globalized society. That's not to say that we are as benevolent as the Utopians and their ideas of an unbreakable truce are; the US specifically has stacked up plenty of war crimes. However, I can see a connection in the notion that the Utopians would regard war with "utter loathing" (98). It speaks to their wisdom and experiences when dealing with war, if not aided by their inherently peaceful nature. With supranational organizations like the United Nations watching over potential warmongering, we have now established Utopian-like preventative measures against war. We have policies in place like sanctions in attempt to keep peace. An all-out war today could result in the complete obliteration of all human life, and it's sad it's taken us until that point to be so hesitant to engage in war. Also, ahead of their time in regards to human rights, "If victory rests with the Utopians, they do not revenge themselves with blood" (103). I'd like to believe that we have become less brutal of a society; we no longer behead people over ideological differences like Henry VIII did to Thomas More. The Utopians were recognize the value of humanity. With the recent suspension of the INF (nuclear) Treaty between the US and Russia and the beginning a new arms race, the world's leaders could look to the Utopians as a reminder of the physical and emotional costs of war.

How much is too much?

Thomas More's Utopia is spectacularly detailed. The level of micromanagement in the conception of Utopian social, economic, political, and military life seems to border on the obsessive, down to specific tactics used in warfare. That is certainly a bonus, given our working definition for Utopian fiction, but such in-depth descriptions are tedious to read. A audience that becomes bored or irritated by a story is likely to put the book down or turn off the movie, rather than paying attention to the message. At what point should intricate world-building give way for the sake of holding the audience's attention?

Wednesday, February 6, 2019

Es muy complicado mi amigo.

Hola mis amigos. Aquí hay una lista de cosas que me resultan complicadas.

1. Spanish. I just dropped Spanish 202. That shits hard, and i'm gonna have to give it another run next semester.

2. Fishing scams at Hood College. How are there so many? And are we just gonna ignore the fact that the man trying to defend us from these scams is named Bing Crosby?! A true unsung hero.

3.The System of Local Government in today's portion of More's "Utopia".

I'm not saying I find chapter 3 good or bad... just that I thought it was a little confusing. It might have just been all the Greek names?

I liked parts. The whole postponement of senate debates thing was funny. More saying he doesn't appreciate when people blurt of the first thing on their mind and then try to defend it. (pg. 64). Kinda sounds like a lot of modern politicians today. I lol'd a little.

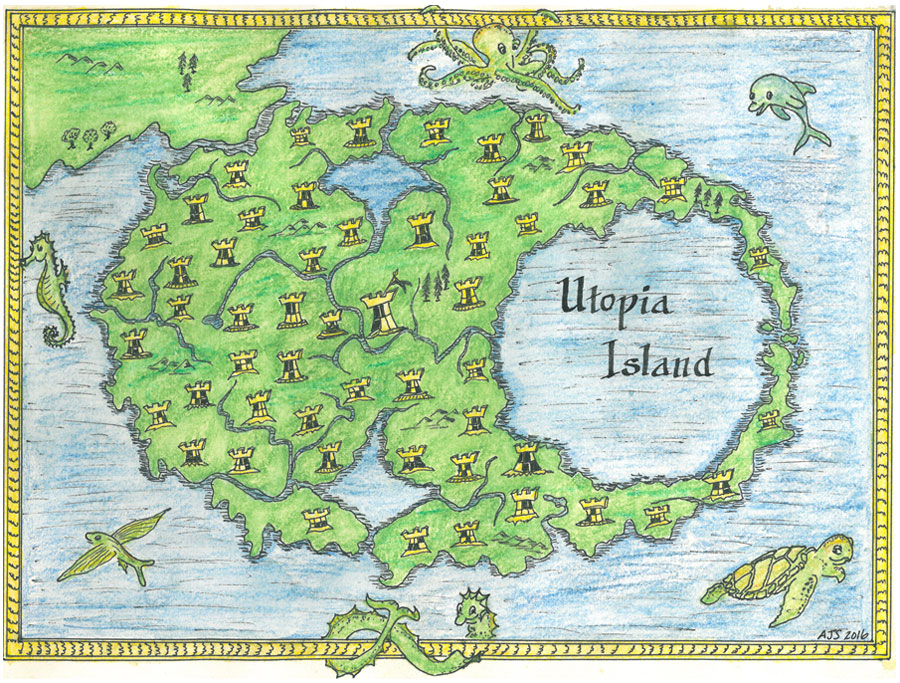

404 Island Not Found

Since Book 2 opens with an explanation of the geography of Utopia, I thought it would be interesting to find an artist's interpretation of what the island might look like. There have been a handful of designs over the years, but I think this one by Andrew Simoson, who applied calculus to the descriptions, might be a more accurate interpretation.

Inside Science article here. Simoson's explanation here.

Inside Science article here. Simoson's explanation here.

Monday, February 4, 2019

Designs of Truth and Nonsense in More's Utopia

As soon as I began reading More's Utopia, I found myself tracking the structure of the text. By establishing a familiar scene (a meeting/feast), readers are encouraged to relax into the dialogue between More and Raphael. The influence of Plato's Republic is apparent, and as such, the discussion of Utopia is broached in contrast to a problem that needs to be solved: England and its noble court. I enjoyed keeping track of the many false or imagined places or terms that appear throughout book one, such as: Polylerites, oligopoly, utopia, Achorians, and ultraequinoctials. The Polylerites are "people of much nonsense," and are used in juxtaposition to the stubborn nobles (More, 41). Their society mirrors that of Socrates' gold, silver, copper, and iron run society. Because of this, I wonder how much of the described England and the briefly mentioned Utopias are meant to seduce the reader with Raphael's arguments - to make us believe that whatever he believes is sensible and correct, as he has 'seen' the impossible world of a utopia. Yet, the dialogue does not serve to bulldoze objections, as More's amused curiosity and warnings highlight the fact that this text is working to encourage questioning of what is right, proper, and desirable in a society. Raphael expressly states that the Utopia's superiority lies within the fact that "their commonwealth is more wisely governed and more prosperous than ours" (More 57). All of this reminds me of our class's circular discussions on what a utopia is and how it can truly be one in the face of human diversity.

In short, I feel that, despite the places and people in book one existing in reality, the constant references to utopia and its laws reveal that this scenario is still imbued with a message and commentary that uses traces of truth to incite conversation and inquiry about peoples' subjectivity concerning 'utopias' and 'Englands' alike.

In short, I feel that, despite the places and people in book one existing in reality, the constant references to utopia and its laws reveal that this scenario is still imbued with a message and commentary that uses traces of truth to incite conversation and inquiry about peoples' subjectivity concerning 'utopias' and 'Englands' alike.

|

| https://i1.wp.com/teacherdavidoh.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/subjectivity.gif |

Slavery in Utopia reflection

Interestingly enough, slavery in Utopia isn’t based upon race, ethnicity, or religious identity. Here, it becomes more of a reflection of circumstance and morality. The idea that free laborers could volunteer as bond men seems so asinine when associated with my idea of slavery. More’s Utopia has a strong emphasis on virtue and community. The people follow customs and practices that seem extremely compassionate when compared to other societies in the sixteenth century, as well as, modern day societies. They are very willing to forgive criminals who have been condemned to death in other countries but have no compassion for Utopian criminals. In fact, they are punished more serverely than any other slave. To some extent this seems backwards, people tend to be more forgiving and lenient to those who are apart of their community as opposed to strangers.

I understand that the justification for this is that Utopians have been brought up in a virtuous community so deviation from the rules is a particularly heinous crime, but I do not believe that there is ever a justifiable reason to enslave a person regardless of what crime they have committed. An action like adultery is punished by enslavement. While I think that adultery is very detrimental, I could not imagine living in a place where the result of a bad decision or action done one time is infinite punishment. The inclusion of concept of slavery as punishment in a novel about a completely fictional and “ideal” society is perplexing. I think the integration of slavery in an idealized society is general, is indicative of the time period and how many societies are built and maintained. It leaves me to wonder if Utopia is just as morally corrupt as any other society because I don’t think that a society that relies on slave labor could really be virtuous.

I understand that the justification for this is that Utopians have been brought up in a virtuous community so deviation from the rules is a particularly heinous crime, but I do not believe that there is ever a justifiable reason to enslave a person regardless of what crime they have committed. An action like adultery is punished by enslavement. While I think that adultery is very detrimental, I could not imagine living in a place where the result of a bad decision or action done one time is infinite punishment. The inclusion of concept of slavery as punishment in a novel about a completely fictional and “ideal” society is perplexing. I think the integration of slavery in an idealized society is general, is indicative of the time period and how many societies are built and maintained. It leaves me to wonder if Utopia is just as morally corrupt as any other society because I don’t think that a society that relies on slave labor could really be virtuous.

Improving Society

Upon reading Book I of More's Utopia, I couldn't help but think about a lot of the attributes that he pointed out about various societies that he thinks makes them superior to his own society. One of them are his views on punishment for crime and whether criminals should be punished with death. He says, about the Polylerites, "those who are convicted of theft repay what they have taken to the owner and, not, as is usual elsewhere, to the ruler, who they think has no more right to the stolen thing than do the thieves. If the thing is lost, the value is made up and paid out of the thieves' belongings, the rest is given to their wives and children, and the thieves themselves are condemned to hard labor." (More, 41)

The servants are fed well and taken care of, and, often the criminals end up being kind-hearted and trustworthy through their hard work and contribution to the society. As More says, "The object of this punishment is to destroy the vice and save the person." (More, 42)

He also discusses how a leader or King should be, and that is that they should be more concerned with the happiness, success, and wealth of their people, rather than their own. If the king only cares about himself, and ends up hated by his people because he tries to control them with oppression and reduce them to poverty, then More thinks it would be better for him to resign from his throne. He says, "For it is not a king's part to reign over beggars, but rather over the prosperous and happy," and, "If one man lives a life of pleasure and self-indulgence amidst the groans and lamentations of all around him, he is the keeper of a prison, not of a kingdom." (More, 50-51)

When thinking about a Utopia, I certainly think these two aspects would be quite important. Reform, instead of punishment, and prosperity for everyone instead of oppression due to greed.

The servants are fed well and taken care of, and, often the criminals end up being kind-hearted and trustworthy through their hard work and contribution to the society. As More says, "The object of this punishment is to destroy the vice and save the person." (More, 42)

He also discusses how a leader or King should be, and that is that they should be more concerned with the happiness, success, and wealth of their people, rather than their own. If the king only cares about himself, and ends up hated by his people because he tries to control them with oppression and reduce them to poverty, then More thinks it would be better for him to resign from his throne. He says, "For it is not a king's part to reign over beggars, but rather over the prosperous and happy," and, "If one man lives a life of pleasure and self-indulgence amidst the groans and lamentations of all around him, he is the keeper of a prison, not of a kingdom." (More, 50-51)

When thinking about a Utopia, I certainly think these two aspects would be quite important. Reform, instead of punishment, and prosperity for everyone instead of oppression due to greed.

Skepticism and Utopia

In approaching the reading, I found myself siding more and more with the lawyer rather than Raphael and I truly couldn’t help it. While reading through Raphael’s thoughts on theft, punishment, and government I too was mimicking the lawyer, “He shook his head, screwed up his face, and held his peace” (More; 43).

I found myself questioning every solution that Raphael came up with only to have it later answered in the next sentence (this can be noticed in any of Raphael’s approaches to the discussions, specifically “-not should we accept Stoical rulings that count all offences equal” (More; 40). This was one of the moments where I felt perplexed, but Raphael picked up all of the pieces and presented an answer that would suffice (I think) on the broad spectrum of government and dealing with crime & punishment.

Shockingly, I found Raphael’s expectation of the lawyer’s reply, “-more careful in repeating what has been said than in answering it, so highly do they regard memory,” shaping up to be very similar to my own (More; 39). I was waiting for Raphael to slip up while reading but I couldn’t put together a solid argument besides one major detail I thought important. While a criminal could have his liberty (eventually) and his punishment would be ‘just’ Raphael says that if a convict tried to run away, “-even then his ear would betray him” (More; 42). How do Utopians adjust to their lives post sentencing if half of their ear is missing and how do Utopians treat ex-convicts? If all are equal in Utopia why would they punish someone permanently and mark them in a way that is recognizable to all other people underneath the founding government.

Though this is an analysis of the reading I am wondering why I approached it with so much skepticism. Did anyone else feel like it was such a departure of our own everyday life that they got a little flustered while reading? It seems impossible that a character from 1516 had all of the answers and solutions that would make the world run a little more… smoothly.

(https://giphy.com/explore/white-guy-blinking)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)